TANGARÁ DA SERRA-MT . BRASIL 55 65 99987-8717 IPactangara@GMAIL.COM

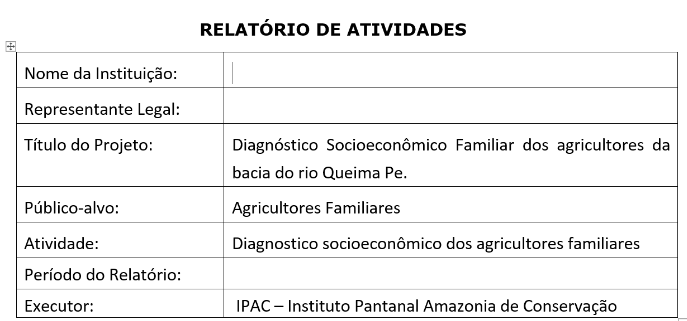

Socioeconomic Survey of the

Queima-Pé Basin

The research was conducted through field research conducted through interviews with farmers from Queima Pé, in the municipality of Tangará da Serra/MT, together with some photographic records.

To carry out this stage, a script consisting of open and semi-open questions was previously prepared. This questionnaire was created and discussed by the Queima-Pé project team. The interview script was guided by three main axes: social, economic and environmental. In order to understand the social conditions of Queima Pé, the following indicators were defined in this study: education, health and housing.

The interview also proposed obtaining information on some indicators that focused on the economic aspects of family farming. To this end, the following points were defined: agricultural production and technical assistance. However, agricultural production in Queima Pé has cultural and climate variations. In order to obtain acceptable information, it would be necessary to monitor the families for a minimum period to form the management of the property. In order to construct a “portrait” of the environmental situation of family farming, the following environmental indicators were studied: work method, water, and disposal of sewage and waste. It is understood that the indicators described above are essential for understanding the current situation of family farming.

The interviews were conducted at the home of each farmer or family.

Objective

Considering the context explained above, this research aimed to analyze the perspective of sustainability in the development of family farming, considering indicators of the social, economic and environmental scope without disregarding elements that are intrinsically linked.

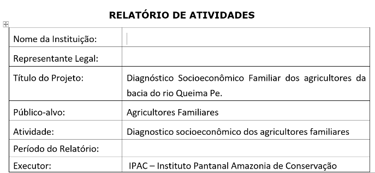

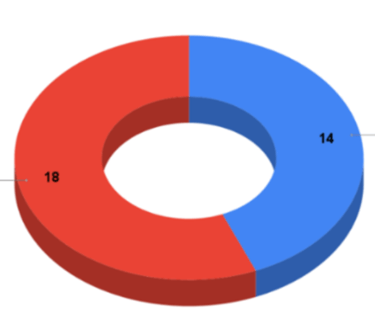

Age range of respondents

As shown in the Graph, the majority of those interviewed were of advanced age.

This factor is interesting, since this is a group of people who generally dreamed of owning their own rural space to raise animals and crops, but mainly thought about improving their financial quality of life. However, this scenario becomes worrying when compared to the number of younger farmers, since young people do not show interest in continuing on the property, leading older people to worry about the future regarding their investments in the properties. However, the participation of a younger audience has become essential in order to compare the perception that these different generations have about the elements that permeate their experiences in rural areas and the increasingly necessary technologies. Older people report difficulties when it comes to accessing courses, online training and often even social media.

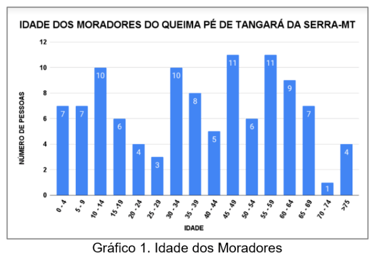

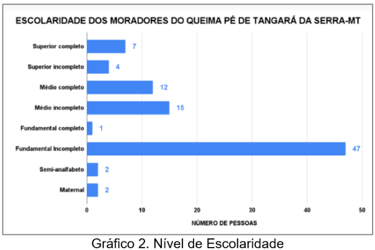

Education

Given the information, we can confirm in the Graph below that the vast majority of those interviewed have a low level of education.

According to the graph above, the level of education of those interviewed in Queima Pé de Tangará da Serra is as follows: only 12 people have completed high school, 1 person has completed elementary school and 47 had incomplete elementary school. 4 people said they were semi-literate and had only completed preschool. This situation is especially aggravated as they get older.

Many of those interviewed made it clear that they wanted to study more, however, most of them, as children of farmers, had to stop studying in order to help with the work on the farm and support their families. This family action was part of their parents' culture or because access to schools was difficult, and during the school years of most of them there was no school transportation in the municipalities where they lived.

Financial conditions, little parental encouragement and the responsibility attributed to young children are difficulties linked to the low level of education. However, they recognize that there are currently no difficulties in accessing education, since school transportation is provided by the local government (Municipal Department of Education).

It can be seen that even with the provision of school transportation, there is a demand that is not met. These are people who study in the municipal headquarters, in higher education, and end up choosing to live in the city or move to the city due to the time.

It is worth analyzing the young people who grew up in Queima Pé and studied at the local school and later started attending school in the city. Over time, they end up getting tired of the daily commute, and when they reach the age to work with a formal contract, they start living in the city, studying at night and working during the day to have a source of income, where they end up starting a family. Given the above, it is clear that the current educational model reduces the prospect of agriculture becoming a “hereditary” issue, as it does not encourage students to live in rural areas, given the noticeable differences in teaching and the structure of physical and human resources between urban and rural schools. Furthermore, there is discrimination in society regarding being a farmer or the son of a farmer, associating these professionals with the image of a country bumpkin, and even with no education.

With the prospect of improving education, it would be interesting to create a full-time school in this region, which would contribute positively to the students who study there. In addition to conventional education, they would have ballet and soccer workshops, among others, and tutoring classes, making it easier for parents who have children with low academic performance and previously took their children to school at least once a week in the second period. The main factors that lead to this conclusion are the stability in the level of education of farmers, the decrease in the number of active schools in rural areas and their physical conditions, and the consequent migration of rural families to urban areas. The facts described above reduce the chances of children, or younger generations, remaining in rural areas. This encourages them to move to the city in search of a “more dignified” form of work and housing, and/or more advanced education.

Housing

Regarding housing, it was observed that 80% (36) of the families interviewed live in masonry houses, while 2% (1) live in wooden houses and 18% (8) live in mixed construction houses.

Regarding the appearance of the housing found in Queima Pé, we can see that the vast majority of families have brick houses with bathrooms inside the residence, one single wooden house and another 8 families live in mixed wood and brick houses. This gives us the impression that the standard of housing found in Queima Pé is relatively good in terms of comfort.

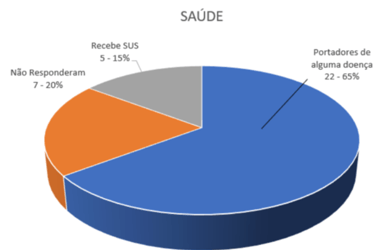

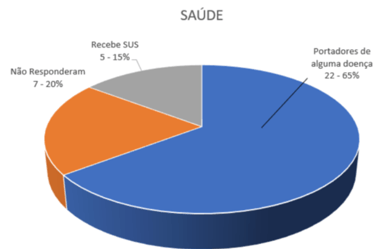

Health

Health indicators in Queima-Pé suggest that community health agents visited most of the homes in the settlement regularly. However, given the current pandemic situation and the lack of visits by health agents to residents, residents are now resorting to the health center located in the city, where they can receive medical, dental, and nursing care, as well as scheduling exams and other procedures. These services are extremely important in the community, considering the age of the population, the existing diseases, and the way producers work, most of whom do not use PPE when handling crop products, cutting equipment, or machinery in general.

The following data regarding the health of residents were found in the survey:

From this data we can conclude that of the 33 families surveyed, 22 have some case of illness, and of this total, 5 receive INSS benefits for illnesses. The remaining 11 families did not report any type of illness or did not respond to this question when requested.

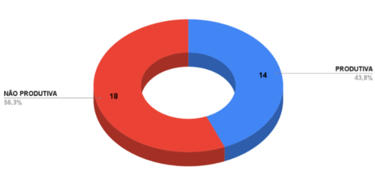

Productivity

According to the research carried out, the following data were obtained regarding productivity in the Queima Pé de Tangará da Serra area: of the total of 32 properties there, 56.3% of the areas are not productive, which corresponds to 18 properties; and only 14 properties, which corresponds to 43.8%, have productive areas.

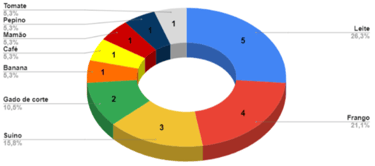

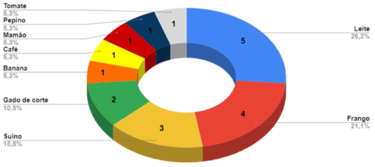

Production/sales

However, the availability of land, water and energy for production, as well as the lack of labor, are factors that contribute to such diversification. In relation to livestock, cattle, pigs and poultry (chickens) were mentioned, as well as the products generated from the raising of these animals, such as eggs, milk and cheese production.

Cattle farming represents 10.5% of Queima Pé de Tangará da Serra's production, represented by 2 beef cattle producers versus 5 dairy cattle producers.

However, in most cases, cattle are sold when the producer slaughters them for his own consumption and sells half of them so as not to have old meat in the freezer or because he does not have enough space to store them, while others are used only to supply milk for the family, or even as a reserve for sale among neighbors. According to these producers, beef cattle require less care, the return is faster, and milk production increases significantly during the rainy season, reaching 40% of production compared to dry periods. The rainy season would be the time when the producer would have a higher profit per liter of milk sold, but during this period the value decreases, affecting the producer's annual average.

When asked about the cost or filling out cost spreadsheets or the amounts paid for inputs, they claim not to have time to fill them out, evidencing a lack of knowledge about the cost of raising livestock. It is worth highlighting that producers do not consider their own labor as a cost, an element that needs to be worked on, and in the future, producers should make it a habit to keep notes on the costs of each individual production.

Poultry farming is the second largest source of income, with 4 producers accounting for 21.1% of production. In addition to the program birds that require specific food, these chicken producers need paddocks and pastures where they raise free-range chickens and slaughter them at home, according to local culture. These free-range chickens are sold at fairs and supermarkets, while the chicken from the slaughterhouse comes in small plastic bags, giving the buyer the impression that they are purchasing an even smaller product. According to producers who sell at the Producer's Fairs, free-range chicken is more sought after because it is larger, is stored in larger plastic bags, and the customer/buyer has greater visibility of the product they are purchasing. Pig production comes in third place, with 3 producers representing 15.8% of Queima Pé Tangará da Serra's production, that is, they sell their products to neighbors and friends by order and at farmers' markets. The animals can be delivered live, ready for slaughter, or slaughtered and cleaned. The slaughter is done at the home itself, without adequate facilities. These producers have higher sales during the end-of-year festivities, when the demand for whole piglets increases.

Vegetable and legume producers represent a total of 2 producers of Queima Pé de Tangará da Serra's production, totaling 10.6%, with significant production of cucumbers and tomatoes.

In conventional farming, vegetables are sold on average at the market for R$5.00 per bunch, while organic farming costs R$6.00 per bunch or head. Products sold in supermarkets are priced lower. Most vegetables and legumes are sold at street markets and supermarkets, but there is no production planning and producers plant according to their parents' teachings, having an excess of product at certain times and a shortage at other times, which makes it clear that producers lack effectiveness in planning and commitment to planting dates. The lack of adequate management becomes a factor in low product quality and excessive losses. Most producers have irrigation, which provides production conditions even in dry seasons. During the rainy season it is also possible to cultivate, but because pests and weeds proliferate more quickly and production declines, producers prefer not to cultivate, even stopping cultivation in January and February. The cost of these products is not calculated by producers. Fruit producers account for 10.6% of Queima Pé de Tangará da Serra's production. There are two producers who sell fruit, including bananas and papayas, which are sold at street markets and supermarkets.

However, there are families who engage in both agricultural and non-agricultural activities. For example, some families have grocery stores, snack and sweet snacks, a bar, and provide services to third parties. Some producers work for their neighbors on a daily basis, while others go to the farms to harvest and return to invest the income in their farms.

It is clear that family farmers are concerned with ensuring the livelihood of their families, whether through the still traditional practice of agricultural production or through activities that can serve as a supplement to their income, which do not necessarily depend on that means for their existence. The option that the farmer makes to carry out activities considered non-agricultural is aimed at increasing family income, since in most cases, that which comes from agricultural production and animal husbandry does not occur consistently due to lack of planning and lack of incentive.

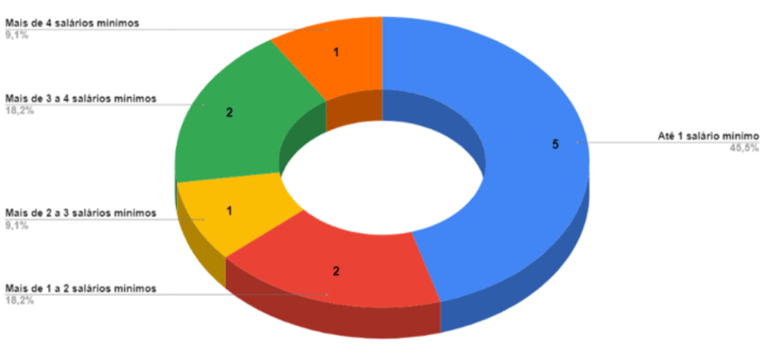

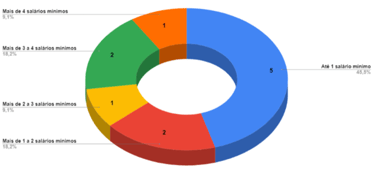

Monthly income from production

The sale of products from the fields and livestock is what represents the income from agricultural activities. Data found through the interviews report the following data: 45.5% of the interviewees (5) receive up to one minimum wage from the monthly production, 18.2% (2) receive between 1 and 2 minimum wages, 9.1% (1) receive between 2 and 3 minimum wages, 18.2% (2) receive between 3 and 4 minimum wages and 9.14% (1) receive more than 4 minimum wages for the monthly production.

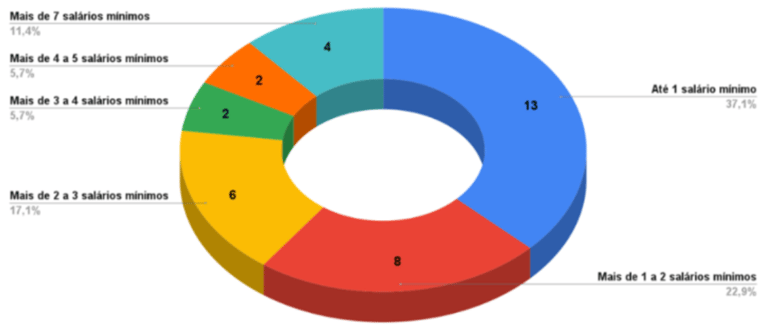

Individual monthly income of the producer

The provision of services, mainly as a day laborer in another agricultural work unit, public office and the sale of handicrafts, cakes, sweets and other products represent non-agricultural activities, however, they generate income. Regarding the income composition of rural families in Queima Pé, it was identified that almost all receive some type of social benefit, be it rural retirement, disability retirement, and/or Bolsa Família. From this income earned through revenue not originating from agricultural production, we arrived at the following data: 37.1% receive up to 1 minimum wage, which corresponds to 13 people; 22.9% (8 people) receive between 1 and 2 minimum wages; 17.1% (6 people) receive between 2 and 3 minimum wages; 5.7% (2 people) receive between 3 and 4 minimum wages; 5.7% (2 people) receive between 4 and 5 minimum wages and 11.4% (4 people) receive more than 7 minimum wages.

Workforce and form of work

On approximately 75% (21) of the properties, the labor force is carried out by the couple and their children or by day laborers. While 7.5% (2) of the properties are managed by tenants and 17.9% (5) of the activities are carried out by hired employees.

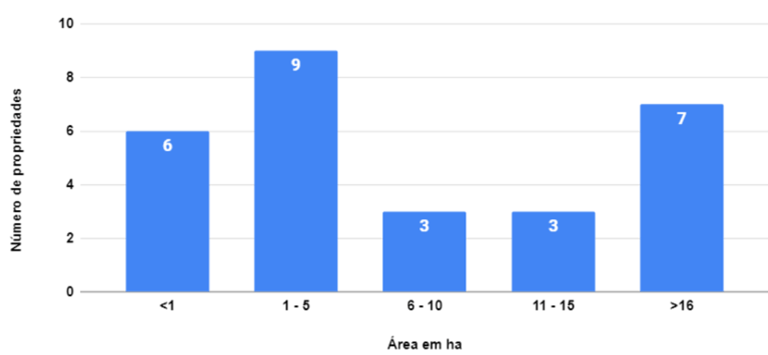

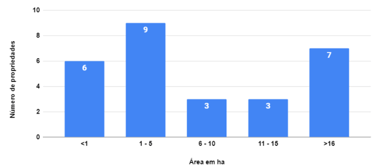

Property area

The size of the property is another element that, according to Law No. 11,326/2006, defines the type of farmer.

Queima Pé de Tangará da Serra has 28 properties, 6 properties with an area of less than 1 ha, 9 properties with an area ranging from 1 to 5 ha, 3 properties with an area between 6 and 10 ha, 3 properties with an area between 11 and 15 ha and 7 properties with an area above 16 ha, as shown in the graph below.

It can be noted that the vast majority can be considered family farmers, except for those who do not have an income from production. Due to the size of the area, it can be said that they are small producers, however, it is not the size of the area that defines the sustainable growth of family farming, but rather the type of soil, water availability and inputs are factors that directly influence production and animal breeding.

It is known from reports that there is a need for investments in soil fertilization, irrigation during dry periods, and other inputs. The creation of new agricultural development strategies to ensure stable food production and environmental quality is becoming increasingly urgent. Among others, the objectives of these new strategies are: food security, protection of the environment and natural resources. These objectives must be in line with local economic sustainability. The equipment used by these actors to carry out their work includes hoes, axes, brush cutters, chainsaws, tractors, among others, and tractors and implements rented from third parties or associations, which were made available by public agencies. Regarding deforestation, it was observed that it is a common practice among family farmers. When asked about the environment, it is usually a subject that producers try not to answer, claiming to have no knowledge about the situations. However, during the interviews, recently deforested areas were seen several times between properties, and sometimes fire and a lot of smoke.

It is clear that it is a tradition for families to opt for deforestation and burning. This fact may be related to the lack of knowledge and/or more sustainable alternatives, environmentally and economically, that could replace such practices.

Both cause major changes in the rural landscape, in addition to contributing to the extinction of animal and plant species, as well as soil erosion, leaving it more unprotected. Furthermore, the smoke from the burning releases gases into the atmosphere that contribute to rising temperatures, making the climate drier.

Another major culprit found on small properties is the inappropriate use of poison. With the large number of pest attacks on vegetables and fruit trees, it is common for producers to apply poison on a daily basis. What is striking is that most of the time, producers do not use PPE, or use it incorrectly. The second point of this use is the way these producers acquire the product, without a technical manager to guide them, they look for local businesses and purchase without further guidance. Often the product is not suitable for the intended use, with a deficiency unknown to the producer, a deficiency that can cause harm to the health of the environment and of the people who handle the poison and the people who purchase the product for food.

Due to a cultural issue on the part of these farmers, they use pesticides as the only way to save production and resist change, even though they know some examples of producers who are able to produce without pesticides, simply by respecting the land. The improper and inadequate use of agrochemicals can cause great economic and environmental damage to society. When used incorrectly, they cause contamination of water and soil, as they move through the environment, through wind and rainwater, to places far from where they were applied. They can also be responsible for the high rates of poisoning observed among producers and rural workers, in addition to causing food contamination. Therefore, it can be seen that if such practices are intensified they will bring serious problems to the environment, which will consequently cause economic and social damage to family farming.

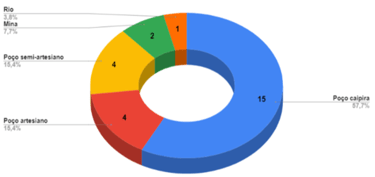

Water

On properties along the Queima Pé Stream basin, approximately 3.8% of properties get their water from the river for consumption, 7.7% get their water from mines, 15.4% are supplied by semi-artesian wells, 15.4% are supplied by artesian wells and 57.7% use rural wells, as shown in the graph below.

In this way, it is easy to see that most of the properties located in Queima-Pé, in Tangará da Serra, use rural wells, with those using artesian and semi-artesian wells representing the second most used form, followed by the smaller group of users who use direct supply from the river and mines.

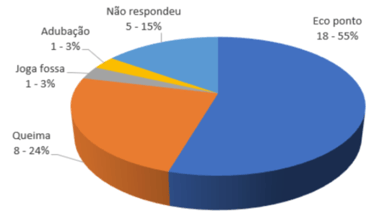

Domestic waste and sewage

Analyzing the situation of the garbage of the families interviewed, four types of destination were identified: burning, use for fertilizer, thrown into septic tanks and transported to a recycling point.

Based on the information obtained from the interviewees, the most common way to dispose of household waste, 55%, is by transporting the material to an ecopoint, followed by burning it (24%), and the rest of the material is thrown into septic tanks and used to fertilize orchards and vegetable gardens.

Some of the interviewees did not respond or were unaware of a more appropriate way to dispose of the waste they generate, and they also stated that they did not see any problems with this method, since the amount generated is considered insignificant by them.

With regard to sewage disposal in the rural area of the municipality, it was clear that all the families interviewed are exposed to open-air domestic sewage.

Regarding sewage disposal, the use of septic tanks predominates. Most of the farmers interviewed stated that they did not see any problem with this method of disposing of water used in domestic services. Others mentioned the emergence of mosquitoes and acknowledged that these can harm the health of their families. However, the number of people who know of a more sustainable method of disposing of domestic and sanitary sewage is greater than the number of people who are unaware of problems arising from the current method of disposal. Sewage disposal in rural areas is unsustainable, making it necessary to consider public policies that promote ecologically sustainable actions to overcome the problem of open-air sewage disposal. The lack of a public policy aimed at improving the quality of life of the rural population, the low income of families and even the form of participation in training and public discussion forums has not led to innovations in family farming in relation to basic sanitation, especially with regard to the sustainable disposal of sewage and garbage. However, alternatives for treating this waste in rural communities must be considered in a participatory manner.

Results achieved

Identification of the main family producers in the municipality;

Collection of data on the families' situations;

Complementing the results of future workshops;

Identification of properties that suffered from fires in 2020.

Institute for environmental preservation and conservation

We defend environmental and cultural preservation.

CONTACT

contato@ipac.org.br

55 65 99987-8717